A 30-year journey to save bluefin tuna

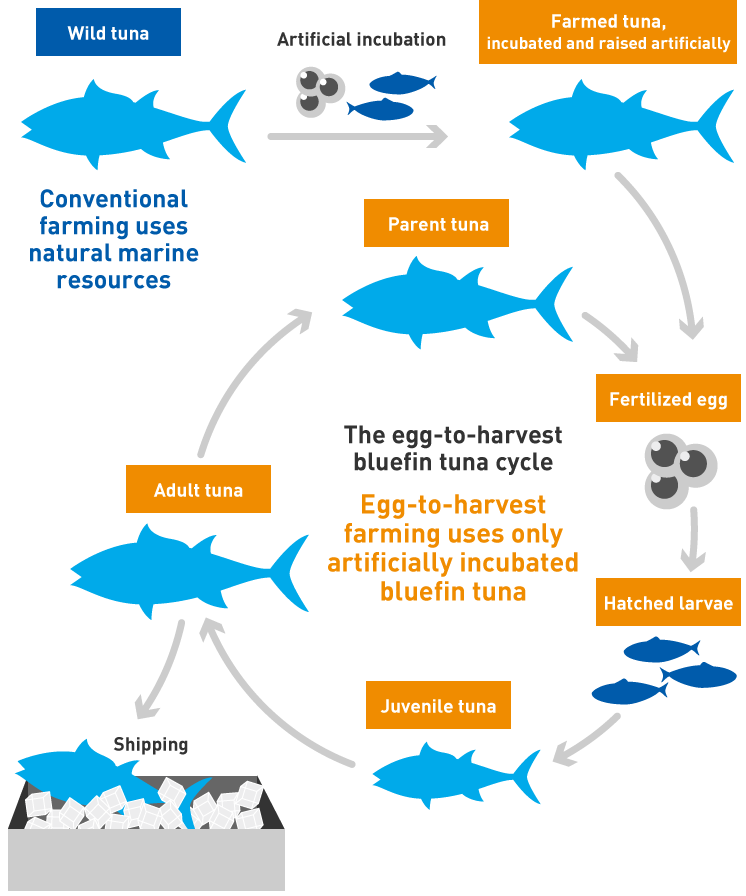

In 1987, Maruha Nichiro began research into 100% egg-to-harvest, farm-raised bluefin tuna. Tuna farming had always been done by catching young tuna in the wild, raising, and breeding them. However, this method cuts off a new generation of tuna by preventing them from breeding in their natural environment. At the same time, marine resources were getting smaller and tuna farming regulations were tightening. Something had to be done.

Nothing is more important to Maruha Nichiro than the health and longevity of the ocean and its resources―so we set out relieve the burden tuna farming put on the environment with a completely new, sustainable method of tuna farming: egg-to-harvest.

At this time, egg-to-harvest farming was still a theory. It was a lofty goal: to successfully recreate the natural breeding cycle of tuna in a closed environment. Egg-to-harvest was about tuna farming―without wild capture. We had high hopes until we learned how complex and sensitive bluefin tuna are. Getting them to breed eluded our scientists.

But that certainly was not the end of egg-to-harvest farming. Some time passed, and technology got better. But bluefin tuna were in trouble. The demand to achieve a sustainable egg-to-harvest life cycle for bluefin tuna grew exponentially.

In 2006, Maruha Nichiro tried again, with renewed confidence. This time we enlisted the help of six universities, which were entrusted with the baseline study. Two fish farms in Amami Oshima were chosen for egg-to-harvest trials because of their expertise in raising young sea bream, and their calming locations on a bay facing the Pacific Ocean.

Trials were underway. For the first few years, most of the time was spent on learning everything there was to know about the biology of young tuna. The research came to a standstill in the past because young tuna did not eat an artificial diet like other fish. On top of that, young tuna could not be observed in their natural habitat. So we had many trial and error experiments in the hopes that we could replicate an environment we couldn’t see.

“Young tuna fish are delicate, so we fussed over vibrations, sounds and light every day. Even then, we found many had died in the morning. We didn’t quite know why and it took a long time to pinpoint the problem.”

After compiling the results of our experiments and various research reports, we eventually discovered an environment suitable for the young tuna to live and breed.

The success was a ray of light. In 2014, it inspired us to scale up to a second egg hatching facility and to create a distribution system that made it possible to raise and move tuna without significant loss. Now we could raise egg-to-harvest tuna in distant farms, outside Amami.

In 2016, we achieved the first full-scale commercial shipping of egg-to-harvest tuna. But there are still challenges ahead. Our goal is to make our egg-to-harvest tuna surpass wild capture tuna in growth, survival rate, and taste.

Check out our video on egg-to-harvest fish farming

November, 2018